Speakers talk about emerging water quality issues such as stormwater management, contaminants in effluent, wastewater in Suisun Marsh, and nutrients discharged into the Bay.

State of the Estuary Conference: Water Quality Sessions

Green Diet for Roads

City of San Pablo project manager Amanda Booth went deep into the nitty gritty on green stormwater infrastructure at a State of the Estuary Conference session. “Talk to the utility agencies before you even start,” she said. “Read PG&E’s Greenbook guidelines. Know your city’s franchise agreements with gas, electrical, sewer, and water companies, figure out who pays to relocate facilities, for example, if that becomes necessary.”

Changing the flow lines of runoff at the street, parcel and regional scale is what stormwater management via green infrastructure is all about. “Regional projects that treat regional drainage are the hardest to site,” said EOA Inc’s Chris Sommer during the session. “To build large stormwater retention projects at a watershed scale you need to use schools, parks, and other larger properties.”

Speaker Terry Fashing reviewed Oakland’s progress on green infrastructure planning. “We’re a city that cares very deeply about our creeks and waterways, and we’re working hard to shift from gray to green across the city,” she said.

Fashing also described the pains Oakland has been going to ensure quality work. The regional water board’s Keith Lichten echoed these sentiments in an earlier plenary. “Make sure the contractor knows what you’re trying to do, they often don’t understand all aims of GI projects. There’s a lot of badly built projects out there,” he said.

Some major transportation upgrades, like the Highway 37 work highlighted by MTC engineer Kevin Chin in another plenary speech, are starting to consider not just environmental impacts and stormwater management, as usual, but also sea level rise and habitat connectivity.

“When you start hearing transportation engineers talk about resilience, then we’re getting somewhere,” summed up the regional water board’s Tom Mumley.

Ingredients in our Effluent

Contaminants of emerging concern, including pharmaceuticals, microplastics, and flame retardants, have little in common beyond the fact that they are not regulated or widely monitored in surface waters. However, they have the potential to harm wildlife or humans, explained Melissa Foley of the San Francisco Bay Regional Monitoring Program during a presentation at the State of the Estuary Conference.

“It’s still a really new concept for people, but we have to rethink our whole water system,” said Kelly Moran, president of San Mateo firm TDC Environmental, in a follow up interview to the conference. “The governor issued an executive order early in his term that basically was challenging us to find new water supplies and take care of all the different waters.”

Foley and others who spoke at the session emphasized source control. It’s “an important strategy for reducing the number of contaminants that make it to wastewater facilities in the first place,” she said.

SFEI scientist Diana Lin presented her comprehensive and groundbreaking new study of tiny plastic fragments in the Bay. “Microplastics are the detritus of modern-day society, where more than 350 million tons of plastics are produced annually.”

Dark Water

In the western Suisun Marsh, you aren’t supposed to see black water, or wastewater. And yet, black water is what you can sometimes see emanating from the managed wetlands of duck clubs in the Marsh, said Stuart Siegel, a wetland ecologist and San Francisco State University professor, who spoke on a conference panel.

“Now that best management practices [to address discharge impacts] have been developed and tested, we can use the practices marsh-wide, working with private landowners on a voluntary basis,” said Steve Chappell, director of the Suisun Resource Conservation District.

Participants on the public and working landscapes panel included staff from other resource conservation districts. Lucas Patzek gave an overview of LandSmart, a program that helps vineyards and other land managers reduce sediment and meet other resource conservation goals.

Alyson Aquino discussed cattle pond improvements in Alameda County. Wendy Rush from Solano County demonstrated through photos the difference between a sterile working waterway and one that is vegetated with native plants and fenced off from cattle.

Future in Nutrient Rush

Estuary managers hope smelt may be revived by the removal of ammonium and other nutrients in Delta waterways. Exactly how these improvements may help declining native pelagic fish in the Delta was the focus of Tamara Kraus’ State of the Estuary conference presentation. “Instead of discharging ammonium, they’ll be discharging nitrate–a significant change on top of the overall reductions,” said the U.S. Geological Survey scientist

Nutrient issues farther downstream were the focus of two other major presentations in the session. The San Francisco Estuary Institute’s David Senn presented data indicating a 30% increase in dissolved inorganic nitrogen loads from the Bay Area’s five largest plants between 2000 and 2017.

Holly Kennedy of HDR worked on a study of 37 wastewater treatment plants around the Bay. “For each plant we identified equipment or basins that could be repurposed, as well as one to three emerging treatment technologies that might help if new regulations on nutrient discharges go into effect.”

San Francisco BayKeeper’s Ian Wren detailed alternative approaches to removing nutrients from wastewater. “The East Bay shore offers the best opportunities for progress on this front, with its mix of potentially high nutrient loads and flood risk, and lands suitable for nature-based solutions,” said Wren.

Nutrient Reduction Strategy Report 2018, BACWA

San Francisco Bay Nutrient Management Strategy

City of San Jose Green Stormwater Infrastructure Plan

Oakland Green Instrastructure Resources

Related Prior ESTUARY Stories

Rainbow Flavors of Blue-Green Infrastructure, Special Issue June 2019

Federal Research Crew Bucks Headwinds & Tracks Nutrients, March 2019

Nudging Natural Magic, Oro Loma Nutrient Removal, December 2017

Nutrient Nuances Modeled, September 2017

Bay Not BPA-Free, September 2019

Next Day Delivery: PCBs, Mercury, Plastics all in One Pacakge, June 2019

LA Drainage Goes Native, ESTUARY June 2017

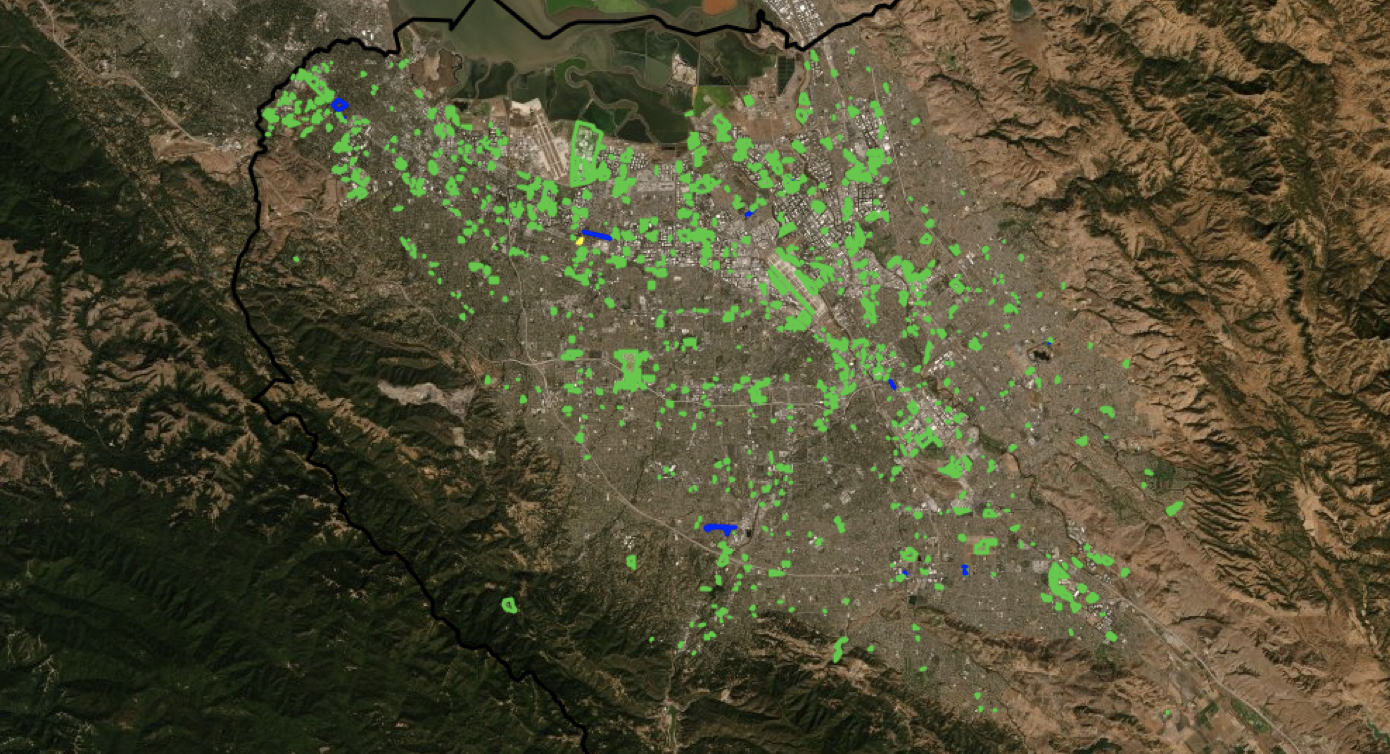

Top Map: Green infrastructure in San Jose as of 2018. Source: EOA/City of San Jose

Special coverage 2019 State of the Estuary Conference

The results are alarming for our state’s future: an estimated four to five feet of sea level rise and loss of one to two-thirds of Southern California beaches by 2100, a 50 percent increase in wildfires over 25,000 acres, stronger and longer heat waves, and infrastructure like airports, wastewater treatment plants, rail and roadways increasingly likely to suffer flooding.

The results are alarming for our state’s future: an estimated four to five feet of sea level rise and loss of one to two-thirds of Southern California beaches by 2100, a 50 percent increase in wildfires over 25,000 acres, stronger and longer heat waves, and infrastructure like airports, wastewater treatment plants, rail and roadways increasingly likely to suffer flooding.